Things Are Starting To Work Out Very Badly For Señor Trumpanzee-- Finally!

- Howie Klein

- Feb 17, 2024

- 8 min read

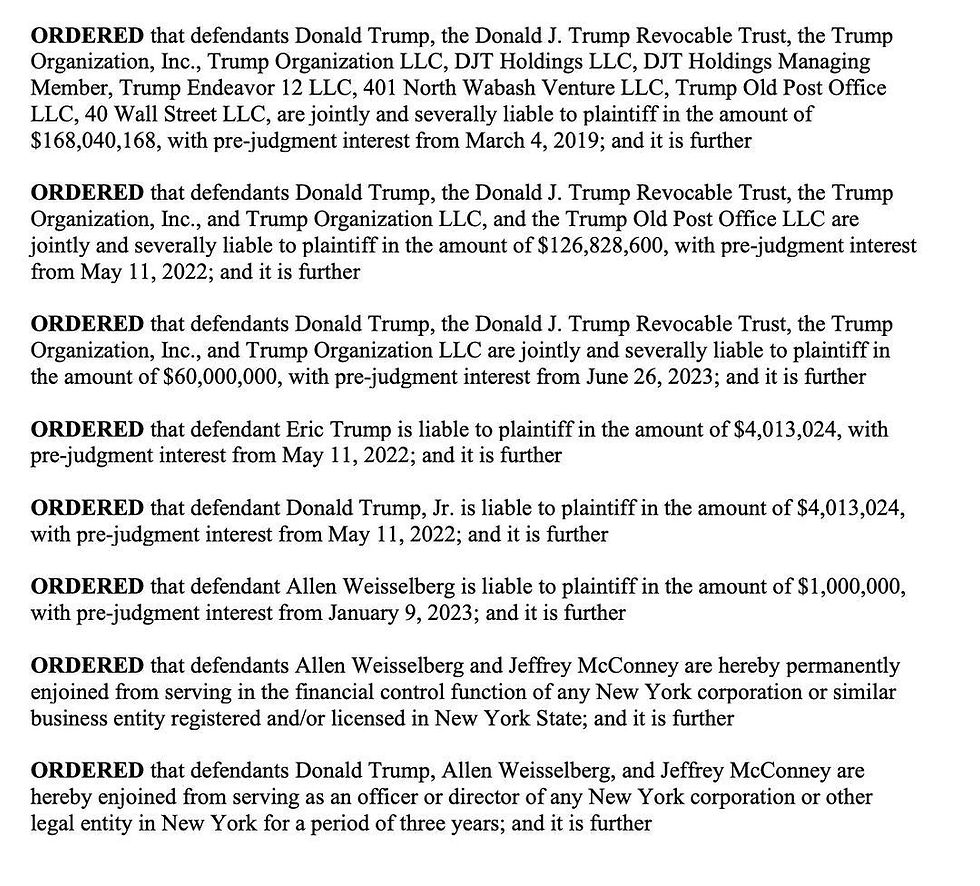

Yesterday, Judge Arthur Engoron ruled that Señor Trumpanzee has to pay nearly $355 million to settle his civil fraud case and that he won’t be able to do business in New York for 3 years. Don Jr and Eric were each fined $4 million and neither of them will be permitted to serve in a top role at any New York company— including, of course, the Trump Organization, of which Eric is now CEO. Jonah Bromwich and Ben Protess reported that Señor T “will appeal the financial penalty— which could climb to $400 million or more once interest is added— but will have to either come up with the money or secure a bond within 30 days. The ruling will not render him bankrupt, because most of his wealth is tied up in real estate… But there might be little Trump can do to thwart one of the judge’s most consequential punishments: extending for three years the appointment of an independent monitor who will be the court’s eyes and ears at the Trump Organization, watching for fraud and second-guessing transactions that look suspicious… The civil fraud ruling comes as Manhattan prosecutors are set to try Trump on criminal charges late next month. He is also contending with 57 other felony counts across three other criminal cases.”

Brett Samuels reported that “Toward the end of his 92-page ruling, Engoron cited the defendants’ refusal to admit to any error.” In retrospect, that seems to have been a big mistake for Trump, although it has worked well enough for him for his entire life.

“The English poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744) first declared, ‘To err is human, to forgive is divine.’ Defendants apparently are of a different mind,” Engoron wrote.

“After some four years of investigation and litigation, the only error (“inadvertent,” of course) that they acknowledge is the tripling of the size of the Trump Tower Penthouse, which cannot be gainsaid. Their complete lack of contrition and remorse borders on pathological,” he continued in his decision. “They are accused only of inflating asset values to make more money. The documents prove this over and over again.”

“This is a venial sin, not a mortal sin. Defendants did not commit murder or arson. They did not rob a bank at gunpoint. Donald Trump is not Bernard Madoff,” he wrote. “Yet, defendants are incapable of admitting the error of their ways. Instead, they adopt a ‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ posture that the evidence belies.”

Trump, wrote Trump scholar McKay Coppins, has always been like this. He watched his first Trump political speech in New Hampshire in 2014 and noted that “he meandered and riffed and told disjointed stories with no evident connection to one another. The incoherence might have been startling if I had taken him seriously. But the year was 2014, and this was Donald Trump— the man who presided over a reality show in which Gary Busey competed in a pizza-selling contest with Meat Loaf. Nobody took Trump seriously.” But Coppins got to spend the next two days with him.

He admits that the article he wrote 36 Hours On The False Campaign Trail With Donald Trump, “cannot exactly be called prescient, in that I rather confidently predicted that my subject would never run for office. But my portrait of Trump— his depthless vanity, his brittle ego, his tragic craving for elite approval— has largely held up. I described him on his plane restlessly flipping through cable news channels in search of his own face, and quoted him casually blowing off his wedding anniversary to fly to Florida. (“There are a lot of good-looking women here,” he told me once we arrived, leaning in at a poolside buffet.) Trump, suffice it to say, did not like the article, and he responded in predictably wrathful fashion. He insulted me on Twitter (‘slimebag reporter,’ ‘true garbage with no credibility’), planted fabricated stories about me in Breitbart News (‘TRUMP: SCUMBAG’ BUZZFEED BLOGGER OGLED WOMEN WHILE HE ATE BISON AT MY RESORT’), and got me blacklisted from covering Republican events where he was speaking. It was a jarring experience, but enlightening in its way. I’ve returned to it repeatedly over the years, mining the episode for insight into the improbable president’s psyche and the era that he’s shaped.”

As the tenth anniversary of my Mar-a-Lago misadventure approached this week, much of the conversation about Trump was focused on his mental competency. There were political reasons for this. Democrats, hoping to deflect concerns about President Joe Biden’s age and memory, were circulating video clips in which Trump sounded confused and unhinged. Trump’s Republican primary opponents had suggested that he’d “lost the zip on his fastball” or was “becoming crazier.” Nikki Haley had called on Trump (and Biden) to take a mental-acuity test. On social media and in the press, countless detractors have speculated that Trump is losing touch with reality, or sliding into dementia, or growing intoxicated by his own conspiracy theories. The sense of progression is what unites all these claims— the idea that Trump is not just bad, but getting worse.

To test this theory, I went back and listened to the recording of my hour-long interview with Trump at Mar-a-Lago in 2014. Half-convinced by the narrative of the former president’s worsening mental health, I expected to find in that audio file a more lucid, cogent Trump— one who hadn’t yet been unraveled by the stresses and travails of power. What I found instead illustrates both the risks of returning him to the Oval Office and the futility of trying to prevent that outcome by focusing on his mental decline: He sounded almost exactly the same as he does now.

This is not to say he sounded sharp. He struggled at times to form complete sentences, and repeatedly lost his train of thought. Throughout our conversation, he said so many obviously untrue things that I remember wondering whether he was a pathological liar or simply deluded.

…Accusing Trump of going crazy doesn’t work because, well, he has sounded crazy for a long time. The people who voted for him don’t seem to mind— in fact, it’s part of the appeal.

Americans, most of whom dread either Biden or Trump becoming the next president, have 3 choices: Trump, Biden or abstaining (staying home or voting for a protest candidate), any of the choices putting either Trump or Biden into the White House again. “Many voters,” wrote David Graham yesterday, “treat elections as a chance to vote a single individual into office; as a result, they tend to focus disproportionately on the personality, character, and temperament of the people running. But voters are also choosing a platform— a set of policies as well as a set of people, chosen by the president, who will shape and implement them. The president is the conductor of an orchestra, not a solo artist. As the past eight years have made very clear, the difference in governance between a Trump administration and a Biden administration is not subtle— for example, on foreign policy, border security, and economics— and voters have plenty of evidence on which to base their decision.”

Graham entertained, for the sake of argument, the two candidate’s mental states. “[I]t’s a little tough to say what exactly is going on with Trump’s mental state. The former president has always had a penchant for saying strange things and acting impulsively, and it’s hard to know whether recent lapses are indications of new troubles or the same deficits that have long been present. His always-dark rhetoric has become more apocalyptic and vengeance-focused, and he frequently seems forgetful or confused about basic facts. To what extent would either of their struggles be material in a future presidential term? One key distinction is that Biden and Trump have fundamentally different conceptions of the presidency as an office. Biden’s approach to governance has been more or less in keeping with the traditions of recent decades. Biden’s Cabinet and West Wing are (for better or worse) stocked with longtime political and policy hands who have extensive experience in government. Cabinet secretaries largely run their departments through normal channels. Policy proposals are usually formulated by subject-area experts. The president’s job is to sit atop this apparatus and set broad direction.”

In contrast to [Biden’s] model of the president as the ultimate decision maker, Trump has approached the presidency less like a Fortune 500 CEO and more like the sole proprietor of a small business. (Though he boasts about his experience running a business empire, the Trump Organization also ran this way— it is a company with a large bottom line but with concentrated and insular management by corporate standards.) As president, Trump had a tendency to micromanage details— the launching system for a new aircraft carrier, the paint scheme on Air Force One— while evincing little interest in major policy questions, such as a long-promised replacement for Obamacare.

At times, Trump has described his role in practically messianic terms: “I alone can fix it,” he infamously said at the 2016 Republican National Convention. He has claimed to be the world’s foremost expert on a wide variety of subjects, and he often disregarded the views of policy experts in his administration, complaining that they tried to talk him out of ideas (when they didn’t just obstruct him). He and his allies have embarked on a major campaign to ensure that staffers in a second Trump administration would be picked for their ideological and personal loyalty to him. Axios has reported that the speechwriter Stephen Miller could be the next attorney general, even though Miller is not an attorney.

Perhaps as a result of these different approaches to the job, people who have served under the men have divergent views on them. Whereas Biden can seem bumbling and mild in public, aides’ accounts of his private demeanor depict an engaged, incisive, and sometimes hot-tempered president. That’s also the view that emerges from my colleague Franklin Foer’s book The Last Politician. “He has a kind of mantra: ‘You can never give me too much detail,’” National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has said. “The most difficult part about a meeting with President Biden is preparing for it, because he is sharp, intensely probing, and detail-oriented and focused,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas said last weekend.

Former Trump aides are not so complimentary. Former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly called Trump “a person that has nothing but contempt for our democratic institutions, our Constitution, and the rule of law,” adding, “God help us.” Former Attorney General Bill Barr said that he “shouldn’t be anywhere near the Oval Office.” Former Defense Secretary Mark Esper described him as “unfit for office.” Of 44 former Cabinet members queried by NBC, only four said they supported Trump’s return to office. Even allowing for the puffery of politics, the contrast is dramatic.

…[S]omeone voting for Biden is selecting, above all, a set of policy ideas and promises that he has laid out, with the expectation that the apparatus of the executive branch will implement them.

Voting for Trump is opting for a charismatic individual who brings to office a set of attitudes rather than a platform. Considering the presidency as a matter of individual mental acuity grants the field to Trump’s own preferred conception of unified personal power, so it’s striking that the comparison makes the dangers posed by Trump’s mentality so stark.

Separately, Graham wrote that “Engoron’s ruling in the civil fraud case is not fatal for Trump’s business empire, but it might be a near-death experience. ‘This Court finds that defendants are likely to continue their fraudulent ways unless the Court grants significant injunctive relief,’ Engoron wrote. Elsewhere he observed, ‘Their complete lack of contrition and remorse borders on pathological.’... Trump’s modus operandi could be catching up with him. A petulant, angry appearance in closing arguments in this case might have been tactically foolish, but it was also a heartfelt demonstration of Trump’s fury that he was on the verge of serious punishment for things he’d been doing for decades.”

Trump responded to the judgment on his fake Twitter social media platform with typical lies and bullshit for his cult followers.

While much of this is useful, it is incomplete. A thoughtful person will see beyond the truncated logic of this.

"I remember wondering whether he was a pathological liar or simply deluded."

I think the consensus must be the former. It's how his pappy taught him and how his idol, cohen, drilled it into him. I suppose it's possible that he's devolved from pathological liar to deluded fucking moron... Shirer made the point that after one hears obvious lies often enough, he learns to believe... whichever it is... does it even matter? THAT answer is no.

“Many voters treat elections as a chance to vote a single individual into office; as a result, they tend to focus disproportionately on the…