-by Denise Sullivan

Joan Baez was a junior at Palo Alto High School when she first heard Martin Luther King, Jr. speak at a conference for young Quakers. She would go on to sing for the non-violent movements for civil rights, social, economic and racial justice and against the war in Vietnam.

“King was giving voice to my passionate and ill-articulated beliefs,” wrote Baez in her memoir. Her “exhilarating sense of ‘going somewhere’ with my pacifism” in the aftermath of that speech would lead her to join King on marches in the Jim Crow south and at the historic March on Washington.

If you don’t already know about Baez’s history as a lifelong activist, you certainly would not get it from a viewing of the ahistorical Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, released in US theaters this Christmas.

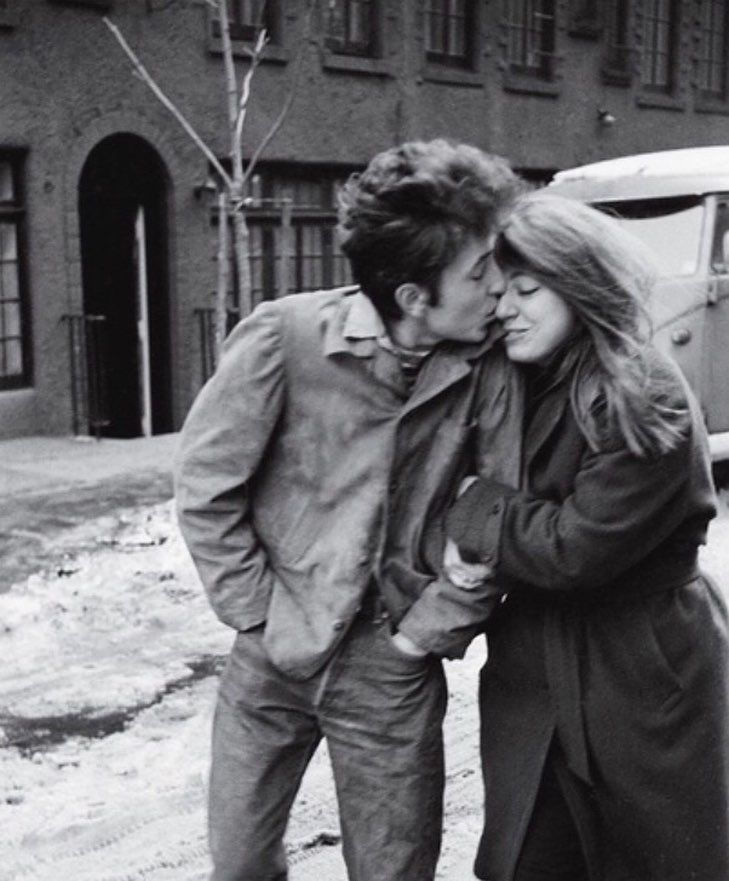

Loosely based on Dylan’s arrival in New York City in 1961, the film covers the songwriter’s introduction to the Greenwich Village scene, his meetings with Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, and his intimate relationships with Baez and the fictional Sylvie Russo, a stand-in for his real life steady, Suze Rotolo.

“During the height of the civil rights era Bob wrote, among other songs, ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,’ ‘The Death of Emmett Till,’ [‘Only A Pawn In Their Game’] and of course, ‘Blowing in the Wind,’ which became a kind of anthem,” Rotolo wrote in her own memoir of the Village in the ‘60s. In the film, “Blowing in the Wind” is framed in his repertoire to be more like an annoyance or an albatross.

There’s a scene recreating Dylan and Rotolo’s meeting at a 1961 folk-a-thon at the Riverside Church, the historic hub of progressive gathering in New York City. And there is a brief moment when the Russo character explains to a befuddled Dylan that she works at the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), organizing the Freedom Rides from North to South— in fact one of Rotolo’s jobs in the era.

Facts are also, that in 1963, Dylan walked off the all-important nationally broadcast The Ed Sullivan Show when he was asked not to play his song, “Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues.” For those unacquainted, the John Birch Society is a radical far right group and the song is a satire.

That not much is made of the realities of the causes and concerns that moved both Baez and Rotolo to become immersed in movement work and the folk scene is perhaps understandable: A Complete Unknown is after all, a version of a story of Dylan becoming Dylan. But the gaps in the story of Dylan’s own connections to civil rights and the songs he wrote in their favor are woefully understated in the film, as are his friendships with the people in his circle (where, for example, were the nods to Ramblin’ Jack Elliott? Phil Ochs? Odetta? Lead Belly, at least, appears in an 8×10 photograph). There are also no poets, comedians or jazz musicians in the film’s version of the Village, though they are among those who also contributed to it being America’s bohemian center of its time.

Nor are there any three dimensional Black artists or musicians depicted in the film. The one scene in which a Black musician has a speaking role was made out of whole cloth and is particularly egregious: The fictional bluesman, Jesse Moffette (portrayed by Big Bill Morganfield whose father in real life was blues legend Muddy Waters) is played as a drunken mess when he appears with Dylan on Seeger’s public television show, Rainbow Quest. That Rainbow Quest really existed and featured musicians Rev. Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee is undeniable. The inclusion of any one of those artists would’ve made an interesting, albeit fictional meeting between Black and white, established and next generation musicians. But the creation of a fictionalized and stereotypical bluesman is not only in poor taste, it was a missed opportunity to introduce new listeners to the musicians who influenced Dylan and generations of future folk, blues and rock musicians.

One full episode of Rainbow Quest was devoted to Dylan’s friend and contemporary, Len Chandler, another figure on the Village scene who was eliminated from the story told in A Complete Unknown. It was Chandler who drove Dylan on the back of his motorbike to deliver his first album to Guthrie in the hospital.

“We took out our guitars and played Woody songs,” said Chandler.

Chandler and Dylan hung out, traded songs, learned their trade and celebrated their song publications in folk journals, Broadside and Sing Out! And while Chandler spent considerably more time in the South fighting for the rights of Black Americans (like Baez, it was his calling), it’s significant that Dylan appeared shoulder to shoulder with both of them at the March on Washington (though the film makes a bungle of computer generated imagery to recreate his appearance there).

Considering what could’ve been is a fool’s game but I’ll play it anyway: Dylan’s first recording session was as a harmonica player on another one of his heroes records: Harry Belafonte’s “Midnight Special.” The often told story of Dylan throwing his harps in the trashcan afterward would’ve made a great cinematic moment. The inclusion of a civil rights giant would’ve again been a nice prompt for a young viewer to dig deeper into Belafonte’s role in American civil rights, music and Dylan’s own history.

Oh but there’s more: Dylan famously had a crush of the wanting to marry her kind on Mavis Staples. Here again, was another missed opportunity to demonstrate how the singer’s dreams listening to and playing music with his inspirers became his reality. Instead, there is a Black woman of intrigue in the film who Dylan dumps in short order after her appearance. We have no idea who she is or is supposed to be standing in for, but a little like the nameless “mistress” played by Angela Bassett in Masked in Anonymous, she is there to let us know the main dude is an equal opportunity romancer.

The studio players on Dylan’s recordings, Paul Griffin, Sam Lay, Bruce Langhorne, as well as his producer Tom Wilson, could all have been elevated to characters with even one or two-line speaking roles, if only to let the audience know these cats were not just extras to add color to the cast: These were seasoned professionals hand-picked for the records that transitioned Dylan from solo folky to serious, original artist.

And then there is the short shrift given to Dr. King, whose “I Have A Dream” speech Dylan and Chandler listened to in real time, on the day it was delivered.

“That’s what I remember from the speech, being behind another monument with Dylan and silencing ourselves, and sitting in amazement as we heard that wonderful speech unfold,” Chandler remembered. But the take on historic Black preaching in A Complete Unknown, comes in the form of a man in a fedora and trench coast on a soap box. Listed in the credits as “civil rights speaker,” the character is but a token symbol for the movement that reached its very apex during the era depicted in the film. The scenes at the Newport Folk Festival would take me another viewing to de/reconstruct but they suffer from similar missed opportunities to display Black excellence and inspiration (Lightnin’ Hopkins, Willie Dixon, Fannie Lou Hamer, for God’s sake).

What could’ve been a simple and effective portrait of young Dylan and the ways folk musicians, women, and Black Americans intersected with the Civil Rights Movement and helped to shape the counterculture and ideals that came to define the ’60s, is in the end, just another piece of product, a part of the Dylan Industrial Complex: The books for days, the several documentaries, a museum and archive, a brand of liquor, a Christmas album, ornaments, and a line of bobbleheads…these are but a fraction of the branded, approved, licensed and unlicensed materials on offer in his name. Why should I have wished that a biopic be anything more than a distraction, an entertainment?

In the end, the contributions to the Civil Rights Movement made by women and Black Americans are the real hidden figures and unknowns obscured in the Hollywood retelling of Dylan’s own early ‘60s story. As impenetrable as the “real Dylan” may be or seem to be, I left the film not thinking about him, but wanting to ask the folks living and passed over, how does it feel?

Denise Sullivan's book, Shadow Dream Chaser of Rainbows, a tribute to Len Chandler, was published in 2024. A portion of sales have been donated to US voting rights organizations.

Comentarios