Ford Paid Up Because It Was Good For Business, Not Because He Was Woke

John Driscoll, a former healthcare CEO, executive at Walgreens and the current chair of a staffing company that manages over 700,000 employees and Morris Pearl, a former Managing Director at BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management firm just released a new book, Pay The People— Why Fair Pay is Good for Business and Great for America after the two of them reached the same conclusion about business: “we need to pay the people if we want to fix what’s wrong with our economy, our politics, and our nation.”

The book argues that, they wrote, “the combination of Congress’ failure to raise the minimum wage and business leaders’ refusal to pay employees fairly is a trifecta failure— a loss for workers, who can’t afford basic necessities like food, rent, and clothing; a mistake for businesses, which can only thrive in the long term when they invest in their employees; and damaging for the economy, which is sustained by consumer demand from the millions of working Americans who are also consumers. We make the case that lawmakers and business leaders need to raise workers’ wages to meet the cost of living if we want to get the country back on a path to stable and inclusive economic growth.”

One lawmaker picked up on it immediately. Ro Khanna: “Raising the minimum wage is not just an economic imperative but a moral one. In this insightful book Driscoll and Pearl lay bare the clear benefits of paying a living wage. They expertly weave together data, personal stories and historical context to make the case for why paying a living wage is critical to creating an economy that is as inclusive as it is vibrant and restoring the American Dream. This book is a must-read for policy makers, business leaders and anyone who cares about building a better future for all Americans.”

This is an excerpt from the introduction of the book:

More than 40 percent of working people in America— over 50 million people— make less than the cost of living for a single person working in low-wage jobs, which include everything from retail clerks to home health aides to cooks. For most of them, especially those with kids, it’s simply not enough to make ends meet.

When you really look at the math, you see that there is a simple solution to what ails the nation, and it can be summed up in three little words: pay the people.

That’s right, the single most efficient, effective (and obvious) way to stabilize the economic lives of working people— and the country— is to make sure that their jobs pay enough so they can meet their cost of living. It is time to reconnect the prosperity of American families to the success of American businesses. When businesses do well, all the people who work for those businesses should do well too— not just the ones in the C-suite. That begins by paying people something close to the actual cost of living. It’s simple. If you can’t afford to pay an employee something they can live on, you can’t afford an employee. If you’re making money while everyone who works for you struggles to survive, you aren’t running a business, you’re running a human exploitation scheme.

Consider this: from 1948 to 1973, productivity rose by 97 percent while hourly compensation rose by 91 percent. During these years, workers received the benefit of increased productivity in the form of higher wages. After 1973, productivity continued to rise, but compensation no longer rose with it. From 1973 to 2014, productivity rose by 72.2 percent while hourly compensation rose only 9.2 percent. Essentially all the productivity gains made post-1973 accrued to the owners of companies rather than the workers themselves. Productivity and compensation became decoupled in the mid-1970s and have remained uncoupled since then. But why? Look no further than the declining value of the nation’s minimum wage.

Stop for a minute here. Stomp your foot on the floor. Now stand up and jump up and down. Did the floor collapse? If so, we’re terribly sorry, but that will teach you how important it is to have a solid floor underneath you. The wage floor is like that. The minimum wage— the wage floor— provides a foundation on which wages much further up rest. Would you rather have a floor with lots of holes in it, or a solid floor that you can jump up and down on? Ask yourself that question every time someone challenges the idea that a strong wage floor is essential to a strong middle class.

Today, there is not a single state in the country where the minimum wage is equal to the cost of living for a single person with no children. Not one. Put another way, there is nowhere in the country where a single person working full-time can support themselves on minimum wage. The “living wage gap,” the difference between what it costs to live somewhere and the hourly minimum wage, is substantial and growing— ranging from $7.89 per hour in Maine to a whopping $16.04 per hour in Georgia. Twenty states with the biggest gaps follow the federal minimum wage of $7.25.

If you want to read the book itself, you can order it through all the regular outlets. Let me recommend Bookshop rather than Jeff Bezos’ company

It was Judd Legum’s question yesterday— What really happened after California raised its minimum wage to $20 for fast food workers— that made me think of Driscoll’s and Pearl’s book. In September 2023, California “enacted a new law that required fast food restaurants with more than 60 locations nationwide to pay workers a minimum of $20 per hour— a $4 per hour increase. The new minimum wage went into effect in April 2024. More than 700,000 people work in California's fast food industry. Almost immediately, Americans nationwide were told the new law would devastate California's fast food industry. In November 2023, before fast food chains in California were even required to pay higher wages, Good Morning America aired a segment warning that customers of McDonald's and Chipotle could be faced with higher prices. In April 2024, Good Morning America ran another piece about the ‘stark realities’ and ‘burdens’ restaurants would face due to the new law. The segment quoted an owner of several El Pollo Loco franchises, who claimed that she would have to ‘reduce hours by roughly more than 10%, simplify menus, and implement new technologies such as automated ordering kiosks.’ An April 2024 piece in the Wall Street Journal, citing two weeks of data after the new wage went into effect, claimed that ‘fast-food and fast-casual restaurants in California have increased prices by 10% overall.’ It also relied on anecdotes from people like John Matthews, a ’62-year-old project manager’ who ‘believes the fast-food wage law is a drag on the state economy’ Matthews told the paper that he ‘shifted his roughly $600 in monthly restaurant spending to independent, sit-down restaurants and away from McDonald’s, Chipotle and other chains.’”

Now, we have actual data about the impact of the law. The Shift Project took a comprehensive look at the impact that the new law had on California’s fast food industry between April 2024, when the law went into effect, and June 2024. The Shift Project specializes in surveying hourly workers working for large firms. As a result, it has "large samples of covered fast food workers in California as well as comparison workers in other states and in similar industries; and of having detailed measurement of wages, hours, staffing, and other channels of adjustment."

Despite the dire warnings from the restaurant industry and some [corporate] media reports, the Shift Project's study did "not find evidence that employers turned to understaffing or reduced scheduled work hours to offset the increased labor costs." Instead, "weekly work hours stayed about the same for California fast food workers, and levels of understaffing appeared to ease." Further, there was "no evidence that wage increases were accompanied by a reduction in fringe benefits… such as health or dental insurance, paid sick time, or retirement benefits."

While workers enjoyed significantly higher wages, the impact of prices was modest. A separate study by the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE) used Uber Eats data to compare prices at fast food chains before and after the new minimum wage took effect. The IRLE study found that prices increased about 3.7% after the wage increase— or about 15 cents for a $4 hamburger.

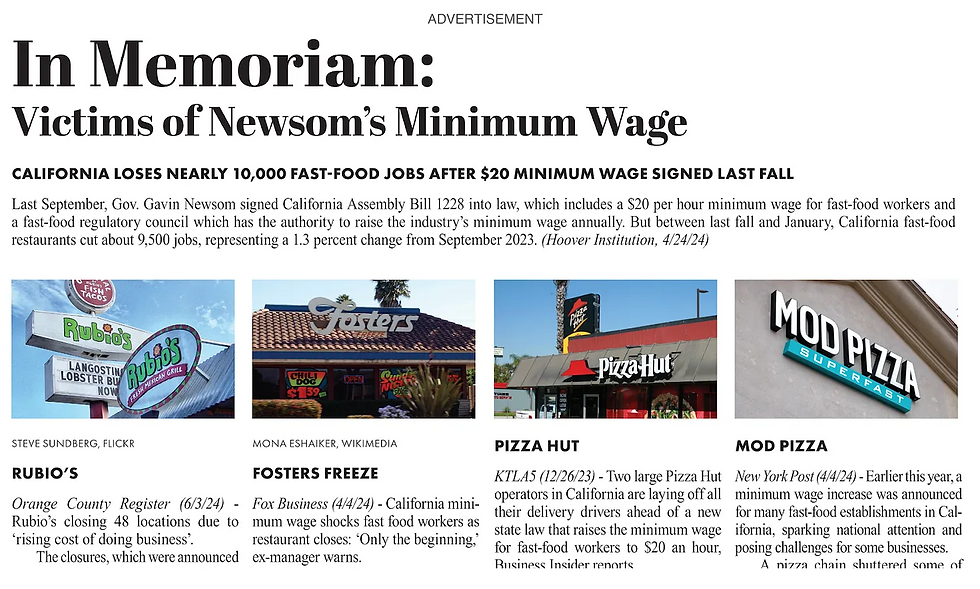

In June 2024, the California Business and Industrial Alliance, an industry lobbying group, ran a full-page ad in USA Today claiming that the fast food industry cut about 9,500 jobs as a result of the $20 minimum wage.

This is a lie.

Notably, the data cited a report by the [right-wing] Hoover Institute in April 2024. But, as Michael Hiltzik noted in the Los Angeles Times, the Hoover Institute report was based on a Wall Street Journal article from March 2024. The Wall Street Journal claimed that, between September 2023 and January 2024, employment at fast food restaurants in California decreased by 1.3% or 9,500 jobs.

The data from the Wall Street Journal covers a period before the new wage went into effect. But the industry claims these job cuts were made preemptively, in preparation for the wage increase. The bigger issue, explained in detail on Barry Ritholtz's blog, is that the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data cited by the Wall Street Journal was not seasonally adjusted.

Every year, there is a modest decline in employment at fast food restaurants from November through January, “when many people travel for holidays like Thanksgiving or Christmas and spend time cooking and eating with family.” So, employment didn't decline between September and January because of the wage increase. It consistently declines during that period every year, which you can see reflected in the red line in the chart below. That's why the BLS offers seasonally adjusted data, represented by the blue line.

Seasonally adjusted data shows that in California, employment at fast food restaurants rose by thousands of jobs during the period covered by the ad.

More recent data is now available, and the trend has continued. According to the BLS data, there were 748,600 employed in the fast food industry in August 2024. That is an increase of 1.9% from August 2023, the last month before the wage increase bill was signed.

Comments