Does It Matter At All?

On Wednesday we took a quick look at the Factory Towns report that examined 11 Great Lakes states, where Democrats are losing working class voters. Yesterday, Ron Brownstein used his Atlantic column to urge the Democrats to look south instead. "Follow the sun," he wrote. "That’s the advice to Democrats from a leading party fundraising organization in an exhaustive analysis of the electoral landscape released today... [arguing] that to solidify their position in Congress and the Electoral College, Democrats must increase their investment and focus on Sun Belt states that have become more politically competitive over recent years as they have grown more urbanized and racially diverse. 'The majority of new, likely Democratic voters live in the South and Southwest, places the Democratic establishment have long ignored or are just waking up to now,' the group argues in the report. The study, focusing on 11 battleground states, is as much a warning as an exhortation. It contends that although the key to contesting Sun Belt states such as North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, and Arizona is to sustain engagement among the largely nonwhite infrequent voters who turned out in huge numbers in 2018 and 2020, it also warns that Republicans could consolidate Donald Trump’s gains last year among some minority voters, particularly Latino men. 'These trends across our multiracial coalition demonstrate the urgent need for campaigns and independent groups to stop assuming voters of color will vote Democrat,' the report asserts."

The states in the study are Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina, Florida, Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, and Texas, as well as Midwest states Minnesota, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

“If all the consultants in the Democratic Party do is follow their same playbook, which is talking only to the most likely voters, or really focusing on white voters or white non-college voters, Democrats will likely lose,” says Jenifer Fernandez Ancona, Way to Win’s vice president and chief strategy officer. “The big message for us is that the core strategy of the 2022 midterm [should be] about engineering and expanding enthusiasm among this high-potential multiracial, multigenerational base that is really a critical part of the electorate across the Sun Belt states.”

...The Way to Win report arrives amid another spasm in the perennial Democratic argument over whether the party’s future revolves more around the emerging electoral opportunities in the Sun Belt or restoring its strength in Rust Belt states such as Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Ohio, and Iowa that have moved toward the GOP in the Trump era. That geographic argument also functions as a proxy for the party’s central demographic debate: whether Democrats should place more priority on recapturing non-college-educated white voters drawn to Trump or on maximizing support and turnout among their more recent coalition of young people, racial minorities, and college-educated white voters, particularly women.

On a national basis, white voters without a college degree for years have been supplying a shrinking share of Democrats’ total votes, both because those voters are declining as a percentage of the overall electorate (down about two percentage points every four years to roughly 40 percent now) and also because Democrats are winning fewer of them, especially in the Trump years.

But that national trend still leaves room for plenty of regional divergence that, in practice, commits Democrats to relying on both strategies, rather than choosing between them.

In the Rust Belt, party candidates have understandably devoted enormous effort to maintaining support among white voters without a college degree. That’s partly because in these states, minority populations are not growing nearly as quickly as in the Sun Belt, and those blue-collar white voters remain about half the electorate or more. But it’s also because a history of class consciousness and union activism has allowed Democrats to historically perform slightly better with working-class white voters in these states than elsewhere, even if that ceiling has lowered amid Trump’s overt appeals to racial resentment.

In the Sun Belt, non-college-educated white voters are both a smaller share of the electorate and more resistant to Democrats, in part because more of them than in the Rust Belt are evangelical Christians. (Although exit polls showed Biden winning about two in five non-college-educated white voters in Michigan, Wisconsin, and even Iowa, he carried only about one in five of them in North Carolina and Georgia and only about one in four in Texas.) Conversely, the opportunity for mobilization is greater in the Sun Belt-- where people of color constitute a majority of the population turning 18 each year in many of the states-- than in the Rust Belt. Given those political and demographic realities, most Democratic campaigns and candidates across the Sun Belt believe their future depends primarily on engaging younger and nonwhite voters-- and the registration and turnout efforts led by Stacey Abrams in Georgia is the model they hope to emulate.

Fernandez Ancona says Way to Win isn’t calling for Democrats to abandon the Rust Belt, or to concede more working-class white voters to the GOP. Rather, she says, the group believes that party donors and campaigns must increase the resources devoted to “expansion” of the minority electorate so that it more closely matches the greater sums already devoted to the “persuasion” of mostly white swing voters.

“I don’t think it’s expansion versus persuasion: It’s that we have to prioritize expansion just as we have historically prioritized persuasion,” she says. “We saw that in 2020. It’s very clear: We needed it all.”

In fact, both Fernandez Ancona and Gavito argue, the entire debate over whether to stress recapturing more white voters or mobilizing more nonwhite voters obscures the party’s actual challenge: finding ways to unify a coalition that is inherently more multiracial and multigenerational than the Republicans’. Even with Trump’s gains among some minority voters, white voters still supplied almost 92 percent of his votes across these 11 states, the analysis found. Biden’s contrasting coalition was much more diverse: just under 60 percent white and more than 40 percent nonwhite.

“Sometimes we are missing the whole and we are not grasping that the multiracial coalition includes white people and people of color, and we have to hold that coalition together,” Fernandez Ancona says. “Thinking about the whole coalition [means] we have to find messages that unite around a shared vision that includes cross-racial solidarity.”

One of those messages, Gavito says, is boosting economically strained families of all races with the kind of kitchen-table programs embedded in the Democrats’ big budget-reconciliation bill, such as tax credits for children, lower prescription-drug prices, and increased subsidies for health- and child-care expenses. Those “programs are very important at this stage,” she says, to give Democrats any chance of avoiding the usual midterm losses for the president’s party, “that’s for damn sure.”

On that point, Biden and almost every Democrat in both the House and the Senate agree. But unless they can also persuade Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona to pass the bill, debates about the Sun Belt versus the Rust Belt, or white versus nonwhite voters, may be washed away by a tide of disapproval from all of those directions.

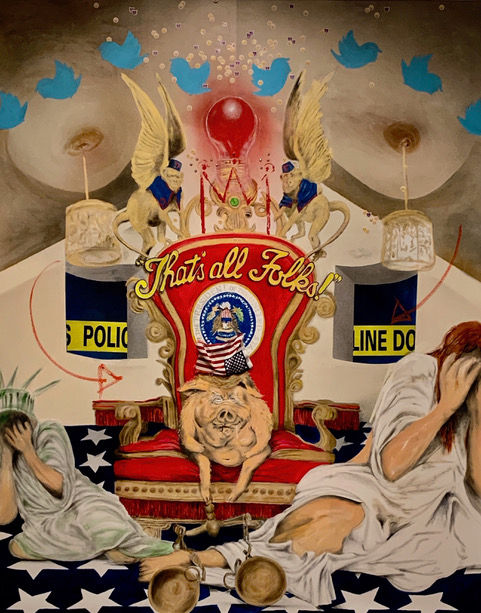

Brownstein is right there. I asked a senior member of Congress about that yesterday and he noted that in another place and another time, Sinema would have fallen out of a helicopter over an ocean by now. Did you see David Leonardt's column yesterday, Taxing The Rich, something almost all Democrats except Manchin, Sinema, Gottheimer, Schrader and the rich ones believe in. Maybe I'm so enthusiastic about the column because it echoes what I-- and other progressives-- have been saying for years: "In the late 20th century, the Democratic Party moved to the right on economic policy. Bill Clinton and his allies in Congress cut taxes on investments, deregulated Wall Street and embraced a more corporate-friendly image. The shift was in part a genuine attempt to be pragmatic about what worked. The United States was faring better than its economic rivals in the 1980s and 1990s, and a market-oriented approach seemed to be a reason. But the evidence has changed in the early 21st century. Economic growth has been disappointingly slow in the U.S., as has income growth for most families. According to many measures of well-being, the U.S. is faring worse than other high-income countries. Life expectancy here has risen less since 1980 than in Canada, Japan, Australia, Britain, France, Germany and dozens of other countries. Soaring economic inequality is a central cause of American stagnation, as the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton have explained. With more years of evidence now available, the turn toward laissez-faire economics in the late 20th century-- including sharp declines in tax rates on the rich-- appears mostly to have helped the rich, not the entire country."

In response, many Democrats have tacked back to the left on economic policy, especially on tax rates for the rich. In 2020, Joe Biden campaigned on raising the income tax, the inheritance tax and investment taxes on the wealthy, as well as increasing the corporate tax (which is effectively paid by stockholders, who are disproportionately wealthy).

When Biden took office, the Democratic Party seemed united in its desire to reverse some of the sharp decline in high-end tax rates. Every Democrat in Congress-- including Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia-- had voted against Donald Trump’s 2017 tax cut. And polls show that most voters support higher taxes on the rich. About 80 percent of Americans say they are bothered by wealthy people and companies not paying “their fair share” of taxes, according to the Pew Research Center.

Yet, now that Democrats hold the White House and control Congress, they are having a hard time raising taxes on the wealthy.

House and Senate Democrats are shrinking Biden’s proposed tax increases, and the party still does not have a consensus on what a final bill should include. The tax plan will probably end up closer to a proposal from Manchin than Biden’s campaign platform.

I asked Gabriel Zucman, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, to estimate the effects of both Manchin’s and Biden’s proposals, and the results are telling:

Why are Democrats struggling to enact an overwhelmingly popular tax increase?

The answer from some frustrated progressives is that centrist Democrats like Manchin have been bought off by the wealthy and their lobbyists. And money does matter in politics. But campaign donations are at best a partial explanation.

It’s worth remembering that left-leaning Democrats today are often better funded than moderates, thanks to a large network of progressive donors. Just look at the fund-raising success of Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, both of whom favor bigger tax increases than Biden. If Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona-- the Senate Democrat most skeptical of tax increases-- embraced Biden’s agenda, they would have no trouble raising money.

A more plausible explanation than campaign donations, Matthew Yglesias of Substack argues, is that Manchin and Sinema sincerely favor lower taxes on the rich than Biden does. Manchin, in particular, often looks for high-profile ways to signal that he is not as liberal as most Democrats. For much of his career, skepticism about high-end tax increases has been an obvious way to do so. He and Sinema are where most Democrats were only a couple of decades ago-- part of what Paul Krugman, the economist and Times Opinion columnist, calls the party’s corporate wing.

Yglesias puts it this way: “Sinema isn’t blocking popular progressive ideas because she’s getting corporate money; she’s getting corporate money because she’s blocking popular progressive ideas, and businesses want their key ally to succeed and prosper.”

In 2021, the Democratic Party’s corporate wing has shrunk so much that it represents only a small share of the party’s elected officials in Washington. Arguably, the group does not include many more than Manchin, Sinema and a handful of House members like Josh Gottheimer of New Jersey. But it doesn’t need to be large to be decisive. The Democrats’ current margin in Congress is so narrow that the party cannot pass legislation without near-unanimous agreement.

If Democrats want to enact larger tax increases on the rich-- and help pay for expansions of pre-K, college, health care, paid leave, clean energy programs and more-- the path to doing so is straightforward: The party needs to win more elections than it did last year.

That isn’t easy, of course. In many conservative and moderate parts of the country, most voters agree with the Democratic Party’s call for high-end tax increases, but have enough other disagreements with the party that they still often vote Republican. And elected Republicans remain almost unanimously in favor of historically low taxes on the wealthy.

If mainstream media are noticing your poor behavior (The View) and calling it out, your voters are eventually going to notice. But Sinema isn't changing her behavior. Analysis from smarter people than me says that Sinema tries to switch parties or goes independent, her re-election chances are poor. Her numbers are already in the tank.

Given Sinema had hardly anything before, and has now made her first million while in office, other things I have read here and elsewhere, my intuition is that financial gain is her first priority. This would mean that she doesn't really care about power per se, she cares about her paycheck.

If Sinema doesn't care what the voters think, it most likely means she believes…

the answer: yes.

it's possible that $inema (and all the rest of the democrap $enate... yes, ALL) would support the money without question.

But the money would never grease up anyone who would not be bought. never.

so... glean what you can, if anything, from the fact that the money greases everyone... both parties.