Yesterday a Des Moines Register poll seems to have finally and definitively answered that question. In 2016, Trump beat Hillary 800,983 (51.15%) to 653,669 (41.74%). Four years later, he beat Biden 897,672 (53.09%) to 759,061 (44.89%)— winning all but 6 of Iowa’s 99 counties each year.

After he lost the Iowa caucuses to Ted Cruz, presaging his sore loser perspective, Trump whined and lied about it nonstop like the stuck pig he is and has always been and will always be:

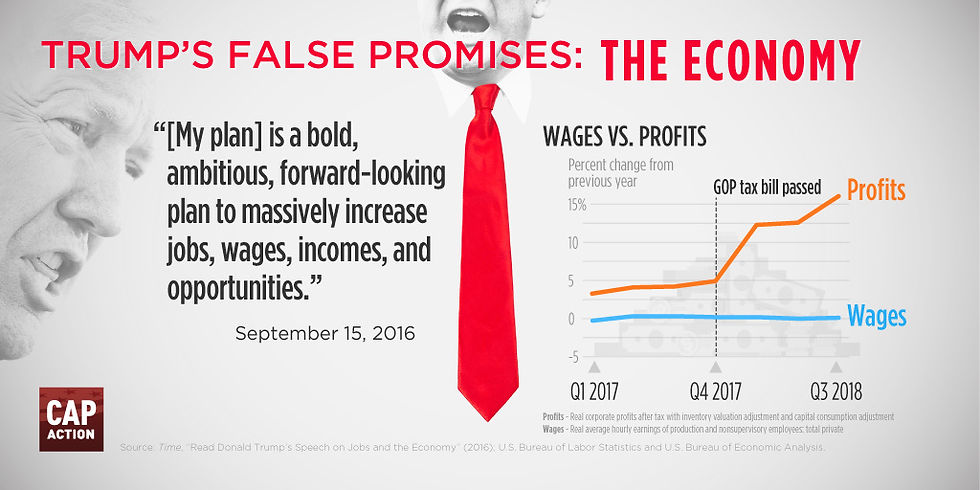

Today, Trump is still whining and lying and still bamboozling Iowans. Critical thinking and legitimate investigation would show them that the economic agenda— which they tell pollsters is so important to them— that Trump is espousing leads directly to high prices, high inflation and lower taxes for high net-worth individuals and big corporations.

Today, The Register’s Brianna Pfannenstiel reported that Trump’s new status as a convicted felon hasn’t dampened Iowans enthusiasm for the NYC con-man who “still holds a double-digit lead over Democratic incumbent Joe Biden in Iowa… 50% to 32% among likely voters... As the candidates move into the general election season, Biden’s approval rating among all Iowans remains low at 28%. Another 67% disapprove of his performance as president, and 5% are not sure... Independents tilt toward disapproval more than 2 to 1, with 69% disapproving and 24% approving of the president’s performance.”

When it comes to inflation, 25% of Iowans say they approve of the job Biden is doing, while 69% disapprove.

… Iowans overwhelmingly believe the country is headed in the wrong direction.

Seventy-seven percent say things in the country have gotten off on the wrong track, while just 17% say things are headed in the right direction.

They hear it on Fox and hear if from the Sinclair right-wing propaganda network. And, some even by reading stuff like this in the Wall Street Journal. Richard Rubin: “The 21% U.S. corporate tax rate is the biggest single variable in the sprawling 2025 tax debate, and the two parties are trying to turn that dial in opposite directions with major consequences for companies’ profits and federal revenue. The rate could climb as high as 28% if Democrats sweep November’s elections and move as low as 15% if Republicans gain full power. Biden’s plan for a 28% rate would reverse half of Republicans’ 2017 rate cut, pushing the U.S. corporate rate back near the highest among major economies. A 15% rate— some Republicans are heading that way, but the party hasn’t settled on a plan— would match the lowest level since 1935, boosting profits and rewarding shareholders. Trump told corporate executives last week that he wanted a 20% rate. Each percentage point is worth more than $130 billion over a decade in tax revenue, creating a $1 trillion-plus gap between the poles of the parties’ positions and giving the largest U.S. companies an outsize interest in the election’s outcome.”

“Why would we want to put U.S. companies in an uncompetitive situation? And if we did that, why would we expect that we would attract investment to the U.S.?” said Jon Moeller, chief executive at consumer-goods maker Procter & Gamble. Moeller leads tax-policy advocacy for the Business Roundtable, the collection of large-company executives who met with Trump last week.

The group is planning an eight-figure spending campaign to support maintaining the 21% rate and extending international tax-law changes that lapse after next year.

The fight over the corporate rate makes up part of the wider tax-policy questions that lawmakers will wrestle with next year as large pieces of the 2017 tax law are scheduled to expire. Also on the table: tax rates for individuals, the child tax credit, the state and local tax deduction, tax rates for closely held businesses and the estate-tax exemption.

Corporations won tax cuts during Trump’s first term, and they would benefit if he wins again. In 2017, many companies pushed for lowering the corporate tax rate to 25% from 35%, aiming for the middle of the pack among peer countries. Trump and congressional Republicans got the rate down to 21%.

Unlike other pieces of that same law, the corporate rate cut doesn’t expire. Republicans were trying to give companies a long-term signal that they could put profits and investment in the U.S. instead of in other countries and get similar after-tax returns.

But tax policy is only as permanent as the political majority that creates it. Democrats tried to raise corporate tax rates after taking power. That plan fell short after Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ) objected, and the 21% rate remained, though Democrats created a separate 15% corporate minimum tax.

Within the Democratic Party, raising the corporate tax is among the easiest political choices, because it generates so much money for other priorities. It lets Democrats direct attention to companies that enjoyed lower taxes and then raised prices; they have pointed to studies showing that the 2017 law yielded modest boosts in investment and delivered wage gains mostly to higher-income workers.

Democrats also point to U.S. corporate tax revenue as a share of the economy as being low internationally; that is misleading because, unlike elsewhere, the U.S. taxes a significant share of U.S. business income on owners’ individual returns, not through the corporate tax.

“The corporate tax share is already low and corporate profits are at record highs,” said Lael Brainard, the White House national economic advisor. “Any way you look at it, we are not raising enough from the corporate side.”

The corporate tax is projected to generate about 8% of U.S. revenue over the next decade, far less than individual income or payroll taxes, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

The corporate tax is one of the most progressive ways of raising revenue, with much of the burden falling on higher-income households, but the reality of who pays it is more nuanced than just saying “companies” or “rich people.” Economists and government agencies generally agree that shareholders ultimately bear much of the cost, with workers and consumers paying some, too. Shareholders, generally, are wealthier than the population as a whole.

The corporate tax is one of the few ways the U.S. can, indirectly, tax foreign investors in U.S. securities and nonprofits with large tax-free endowments.

But the shareholder base also includes pension funds, 401(k) accounts and some middle-income households. Biden and Democrats play down effects on those groups. They also don’t count corporate tax increases as violating the president’s pledge to protect households making under $400,000 from tax hikes.

Republicans and executives see the 21% corporate tax rate and accompanying changes to international tax rules as successful. They note that no U.S. companies have inverted— taken a foreign address for tax savings— since 2017 and they warn that a higher rate would harm the economy. That is a change from the prior few years, when companies such as Johnson Controls and Medtronic inverted.

Higher rates now would be more onerous than a decade ago, Moeller said. That is because the 2017 law broadened the tax base, removing tax breaks such as one for domestic manufacturing, so a 28% tax now would be 28% on more income.

Lawmakers are just beginning to weigh trade-offs within the corporate tax system and the tax code more broadly.

Democrats aren’t necessarily united behind Biden’s 28% rate. Rep. Richard Neal (D-MA), likely the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee if Democrats win a House majority, said he still likes the bill his panel approved in 2021. That had a 26.5% rate, along with international-tax changes that companies sought and higher minimum taxes they opposed. Rates aren’t all that matter to companies, Neal said.

“The rate is the advertised number,” he said. “The deductions and exclusions frequently become more important to them.”

Senate Finance Committee Democrats will meet soon to discuss the 2025 tax debate, and Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) said he is still in wait-and-see mode on Biden’s call for a 28% rate.

However, he said: “It’s interesting when I hear from some corporate CEOs who argue for a competitive tax rate but then also complain about our $34 trillion debt.”

Republicans don’t have a fixed plan, either.

“I’m not going to get pinned in a numbers game,” said Rep. Jason Smith (R-MO), chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. Smith has said some Republicans might want to raise the rate.

“I would go lower,” said Rep. Ralph Norman (R-SC). “Taxes— I don’t care what the liberals say— taxes let people spend their own money, incentivizes our economy.”

Trump’s 2017 tax cuts were a giveaway for the wealthy that exacerbated income inequality while depriving the government of revenue for public services. Raising the rates on corporations and on the super-rich is a step towards ensuring that corporations contribute a fair share to the economy, especially given their record-high profits.

The 2017 tax cuts did not significantly boost investment or wages for average workers, with most benefits accruing to higher-income individuals and shareholders. Raising the corporate tax rate could help reorient economic policy towards broader societal benefits rather than disproportionately favoring the wealthy.

Maintaining or lowering the corporate tax rate, as some Republicans are eager to do, prioritizes corporate profits over public welfare. Economic justice demands that corporations and the wealthy should contribute more to address societal needs, especially in light of the public’s growing discontent with economic inequality and corporate influence in politics.

Dan Pfeiffer noted yesterday that “While inflation has come down and the recent spike in gas prices has largely abated, prices remain higher than when Biden took office. At this point, it seems unlikely there will be a dramatic shift in how people view the economy before they start voting. And not much can be done to make such a shift happen. Regardless, Dems should not concede to the idea that the economy is a failure. Democrats must continue to tell the story of the Biden economy— especially with the currently undecided Biden 2020 voters, most of whom cite the economy as their top issue and incorrectly believe Biden has done very little… [I]t’s time we shift our focus from how the economy is right now to how it will be if Trump wins. It’s time to define Trump’s economic agenda.”

He explained that Señor T “doesn’t really talk ‘policy.’ He prefers the rollicking tales of grievance that get his rally-going supporters fired up. The absence of policy is deliberate, and not just because he has the intellectual curiosity of a shoe horn and the attention span of a fruit fly. It’s a strategic move— his agenda is unpopular and he wants the focus to be on Joe Biden. Trump can win a referendum on Biden, but a choice between two candidates is a much taller order. Over the weekend, two stories shed some critical light on Trump’s economic agenda.

First, the New York Times looked at the core elements of Trump’s economic agenda— renewing the tax cuts passed in his first term, a mass deportation effort, and a 10% across-the-board tariff on all imports— and concluded that:

Trump has offered little explanation about how his plans would lower prices. And several of his policies— whatever their merits on other grounds— would instead put new upward pressure on prices, according to interviews with half a dozen economists… As a matter of textbook economics, each of those three signature Trump policy plans would be likely to raise prices. Some could even cause continued, rather than one-time, price increases— adding to the possibility of inflation.

The inflationary impacts of tax cuts and changes in immigration policy may be challenging to explain to voters. However, there is a very easy way to talk about the tariffs. A study from the Center for American Progress found that:

The proposed across-the-board tariff would amount to a roughly $1,500 annual tax increase for the typical household, including a $90 tax increase on food, a $90 tax increase on prescription drugs, and a $120 tax increase on oil and petroleum products. This tax increase would drive up the price of goods while failing to significantly boost U.S. manufacturing and jobs.

In other words, one of Trump’s first moves— one that doesn't require Congress action— would cost your family $1500.

Second, the Washington Post reported that, in addition to renewing the Trump tax cuts that overwhelmingly benefited the wealthy and expire at the end of next year, Trump’s advisers are considering even lower rates and more breaks for the wealthy and corporations.

To pay for these tax cuts, Republicans plan to cut Social Security and Medicare and repeal the Affordable Care Act.

…Voters overwhelmingly say that the economy/inflation is their top issue. More than 75% of them say the economy is bad and they trust Trump more on economic issues by margins as large as 20 points. To be reelected, Biden doesn't need to win on the economy, but he can’t lose by 20 points.

Therefore, there is tremendous urgency in taking the economy fight to Trump. The best political attacks do two things: erode the opponent’s strengths and exacerbate their weaknesses. A message that makes Trump the candidate of higher prices and tax breaks for the rich checks both boxes.

Let’s circle back around to Iowa with a look, courtesy of Bryce Oates and Jake Davis, at the draft of the GOP farm bill, which passed the House Agriculture Committee, 33-21, with the help of 4 conservative New Dems— Sanford Bishop (GA), Yadira Caraveo (CO), Erik Sorensen (IL) and Don Davis (NC).

“Republicans,” wrote Oates and Davis, “will say anything— and use legislative budget tricks—to cut SNAP. Many House Agriculture Republicans falsely attempted to portray their proposed $27 billion cut to SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as ‘food stamps’) as a preservation of the status quo. GOP SNAP cuts would, in fact, begin in 2027 under their proposal. More than 40 million poor and working class people currently depend on monthly SNAP grocery benefits to put food on the table.” By supporting these cuts, Bishop, Caraveo, Sorensen and Davis are indicating that, like Republicans, they have other priorities than the well-being of poor Americans. “Over the past several years, many populist Democrats have grown more concerned about corporate power in the food system straining the [bipartisan agriculture] coalition. The ongoing crusade against SNAP by House Republicans seems to have fully broken this ‘consensus,’ repeatedly causing long delays and uncertainty during the 2012-2014, 2018 and current farm bill debate cycles.

Oates and Davis added that “In order to pay for their proposed increase to farm subsidies, the House Agriculture Republican draft limits the Secretary of Agriculture’s discretionary Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC) budget authority. The CCC is a government-owned corporation created in 1933 to protect farm income and prices. The House committee draft limits the Agriculture Secretary’s discretionary CCC spending power. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) calculates that the CCC provision would result in a mere $0-$8 billion in deficit reduction. Defiant House Agriculture Republicans claim, without evidence, that their CCC reforms would save $53 billion. That’s a big gap, and fiscal hawks and Democrats are likely to point this out in coming debates.”

They concluded that “Even with its increase in farm subsidies and SNAP cuts, the House Republican farm bill does little to address corporate power, decrease pollution or narrow the gap in farm bill benefits between Monopoly Farmers and the hundreds of thousands of farmers left out of the House draft. The Thompson draft fails to strengthen the Packers and Stockyards Act and ignores checkoff reform. The committee markup also limits state and local government authority to enact environmental standards more strict than federal rules, a provision long sought by corporate meatpackers and Monopoly Farmer factory farms. The budget deal mandating a ‘cost-neutral’ Farm Bill is the core impediment to re-authorization. The biggest challenge to passing a farm bill remains a bipartisan budget deal that caps federal farm and food spending. That cap creates a zero-sum political stand-off between agribusiness and their Monopoly Farmers versus everyone else: the poor and working class, those fighting climate change, struggling rural communities and millions of farmers who receive few (if any) benefits from the farm bill status quo.”

Comments